Benford's law

Once upon a time

In the long-ago, FogBugz stored binary blobs in the database. This made sense, as the database was where all your data was stored. Taking a full backup of a customer site was easy: just take a backup of the customer’s database.

However, for FogBugz On Demand, this meant the most powerful computers were spending time filling up and streaming data from their disk drives. It didn’t make sense to have these high-performance query-munching monsters wasting IO time and (very expensive) disk space storing infrequently-accessed blobs. To scale the FogBugz service, there needed to be two different storage types: lightning-fast structured relational data, and a not-much-slower bucket o’ blobs.

Project Chewbacca

Project Chewbacca began in 2011 as an intern project, to move attachments and raw emails from SQL Server to a distributed, fault-tolerant data store. Fog Creek decided to run this data store inside the FogBugz datacenter, and MogileFS was growing in popularity - a 3-tier system, consisting of a MySQL database, a Perl tracker application, and the file storage nodes. For high availability, MySQL ran in a replication mode, the tracker application ran in pairs, and there were three file storage nodes. The tracker ensured that each file was stored on more than one storage node. An rsync cron job took nightly off-site backups of the MySQL database and the file storage nodes.

Of course, this did make customer data requests more complicated, as now SQL backups also had to have all the files added to them somehow. The database export tool got an upgrade, to support backfilling all the attachments to customer database backups before sending it to them. From the user’s point of view, nothing had changed. Files were still uploaded and downloaded from FogBugz, and database backups still contained everything needed to migrate to FogBugz For Your Server, archival, or a competitor.

Content-addressable storage

The first iteration of this project was a smashing success – it reduced storage needs on the SQL Server boxes significantly, and database growth became much more predictable. Unfortunately, the Mogile growth was also predictable: it was still consuming drive capacity faster than we had hoped. Further analysis determined that many of the attachments were identical to others. A major source of this repetition was from emails. For example, some companies require that their employees include logos in the footer of their emails, and FogBugz was storing each one of these identical images every single time. And some email clients would keep the logo attached in the reply, causing a copy to be stored in FogBugz for each RE:, CC:, and FWD:. The solution to this duplication was to calculate the SHA hash of the file, and make identical attachments resolve to the same file in the Mogile cluster. This helped reduce the storage utilization and growth, so there was no reason to provision any new hardware for years.

Bucket's Edge

Inevitably, the Mogile cluster finally filled up, and the heroes of the Fog Creek sysadmin team spent many hours replacing one hard drive at a time and waiting for the cluster to rebuild, in order to double the storage capacity of the cluster.

Last year, faced with the prospect of error-prone manual labor, in a state none of us live in, my distributed team of developers and infrastructure engineers had to make a decision: should we spend hours swapping drives in New York, or was there a better way? What we came up with was called Bucket’s Edge: updating FogBugz to use AWS S3 to store and serve attachments and raw emails to customers.

I think we made some very smart decisions, like using cross-region replication in case us-east-1 completely disappears. But there’s one unexpected phrase in the technical spec:

The key starts with the SHA256 hash of the ASCII-encoded customer number.

Why did I write that?

Benford's law

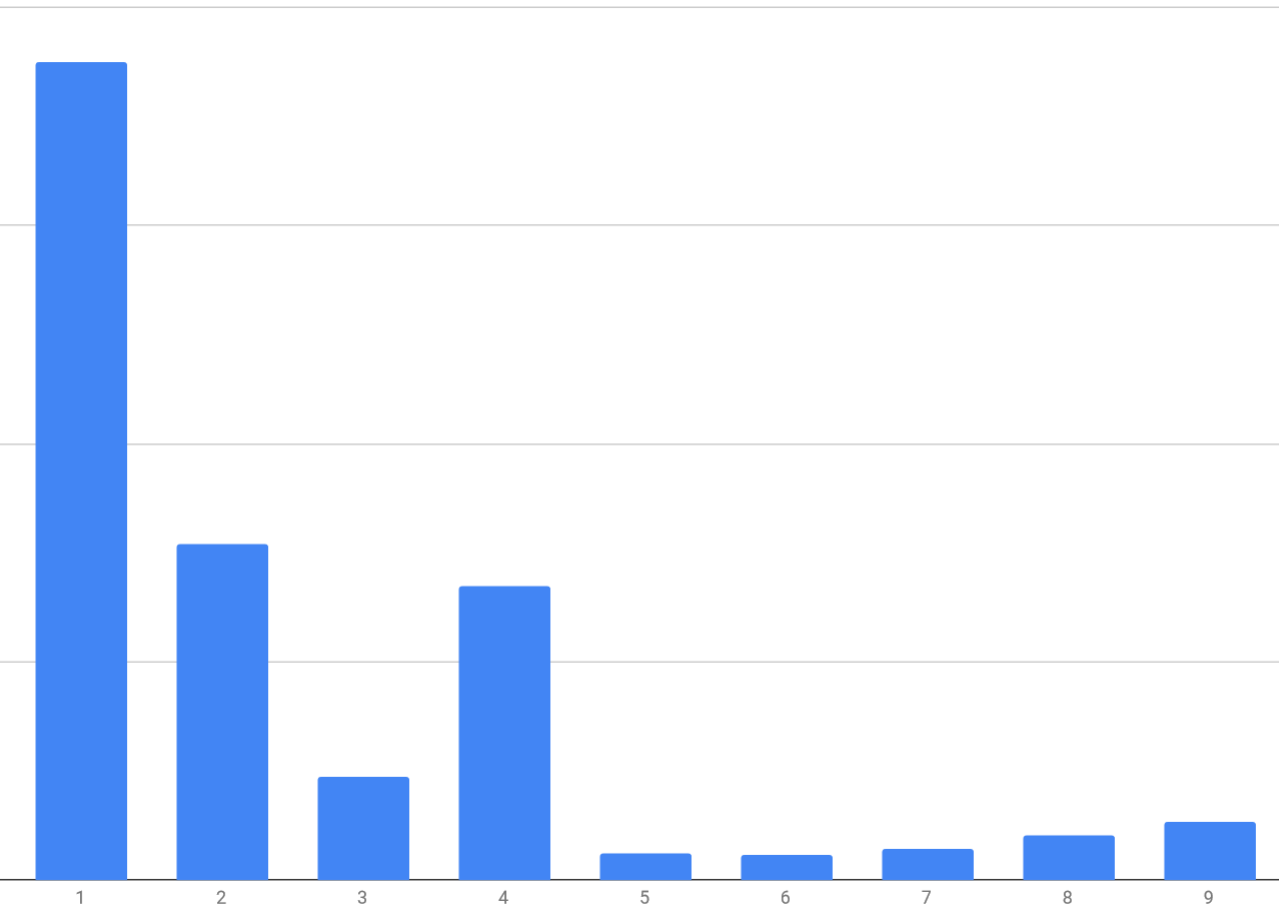

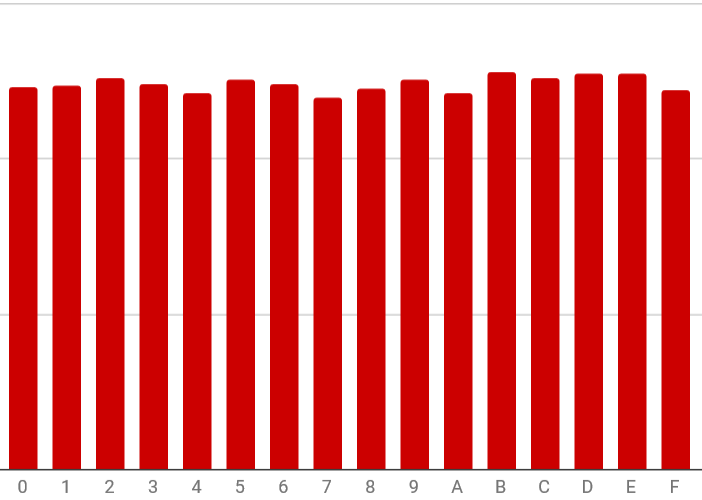

S3 objects are partitioned by key prefix. If we used the customer number, Mr. Benford told us, a higher-than-expected number of customers would end up in the 1 bucket, and a lower-than-expected number would end up in the 9 bucket. (None would end up in bucket 0.) Using SHA256, statistically we would expect each digit of customer’s prefix would be evenly distributed among the sixteen hexadecimal digits.

Looking at the actual customer numbers, this is in fact true. Almost half of all customer numbers start with 1. And almost 90% start with one of the first four digits. This meant that, if FogBugz customers started requesting a lot of data at the same time, half of them would be stepping on each others’ toes, while the other half would be blissfully unaware of the traffic jam.

And with SHA256, there is an almost even distribution of leading characters:

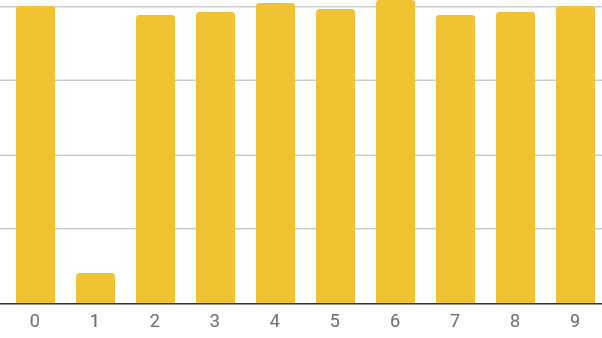

Another option would have been to store the customer numbers reversed (e.g. customer number 1234 would be stored with prefix 4321). This would give a fairly good distribution, except for the lack of trailing 1s, which is surprising and requires more investigation:

However, I chose to use a hash algorithm because otherwise it would be too easy for a human to accidentally make a mistake when entering a customer number and, for example, delete all of customer 45436’s attachments when they meant to delete all of customer 63454’s! The SHA256 algorithm makes it clearer to a human operator that they need to perform some calculation first.

Bucket’s Edge has several other nice features, including that downloading and uploading attachments is now directly between AWS and the user, rather than using our datacenter’s relatively tinier bandwidth allocation, and that disaster recovery backups and failovers can be done much more quickly as well. But I thought this application of 19th century statistics discoveries to modern high-performance web applications was quite interesting.

Plus ça change

Of course, all of our smart design has been out-smarted by Amazon. Remember when I said “S3 objects are partitioned by key prefix?” That is no longer true, since Amazon S3 announced drastically increased request performance on July 17. Object partitioning is now performed on the entire key prefix, not just its leading characters. So, if I had just specified that the prefix was the customer number to begin with, then waited about a year, we wouldn’t have had to hash anything at all, and we’d have exactly the same peak performance we do now.

Lessons learned

- Relational database servers should store structured data, not blobs.

- Deduplication reduces redundancy and repetition.

- Many distributions of numbers follow a peculiar distribution of their first digit.

- Reversing numbers avoids this peculiarity, but might cause transcription mistakes.

- Fast hash functions like SHA256 work well

- Cloud services often improve faster than in-house services.